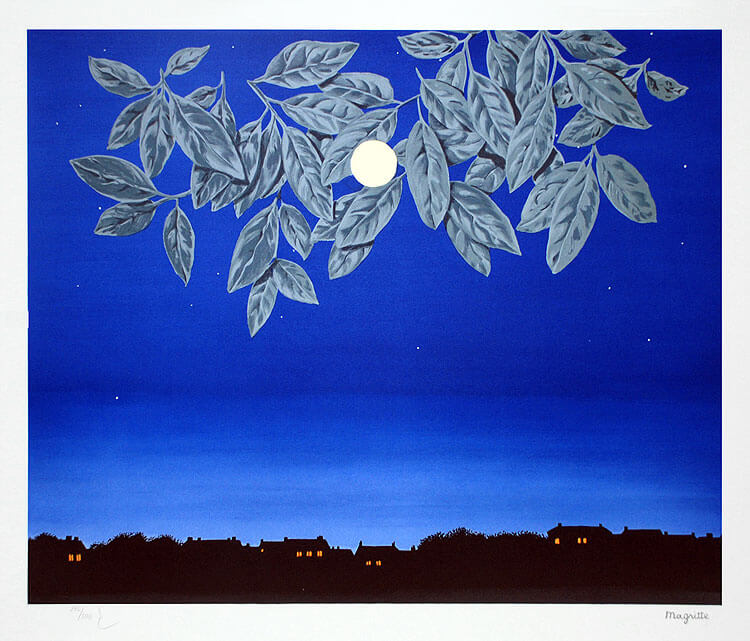

La Page Blanche & Georgette (Affiche)

Kathleen Rooney

La Page Blanche

The white page, it’s called, but it’s endings and twilights. It’s a moon that’s full in impossible looming: the same height as the leaves like some kind of citrus, in front of the greenery as opposed to behind. The city, with lights both on and off, lazes under stars, and Georgette imagines a calmness the image can neither deny nor corroborate: crickets, yes; cars, no.

It’s the last finished work her husband achieved before this limbo of his final illness: that messy and smelly unexpected inevitable. It wasn’t supposed to happen this way: a sudden last collapse. But who ever thinks it happens how it’s meant to?

The beauty of the yellow circle reminds Georgette of her husband’s unbeautiful jaundice; his traitorous pancreas. It’s August now and when September arrives, it won’t have Mag in it. They are at a window together and on the other side for him lies a white page, she guesses, and for her that field of unknowable size that’s known as “widow.”

She sits by his bedside. Their bedside. He is going to die there. He’d been reading, on and off throughout his life, Mallarmé, and the book stands sentry atop their shared nightstand. Now, at the end, it’s not a bed he shares with her, but with his cancer. Mallarmé devoted his thoughts to how writing can’t preserve the whiteness of the page. Georgette devotes hers to how no one can preserve anything.

Loulou their Pomeranian does not incline to yappiness—their dogs have always been well-behaved—but his unhappiness, too, must find expression and he curls on the floor, fluffily whining. The words they need might not exist. How Mallarmé-ian.

Georgette holds Magritte’s hand, which at any moment may cease to contain him. She feels like an empty gown, white as peppermint. In France, white nights refer not to midnight sun, but to insomnia. Georgette maintains a sleepless vigil while her husband stays unconscious most of the time.

“I too like to see leaves hiding the moon, but if we saw some behind the moon, it would be unheard-of, life would finally have a meaning!” René had said in the studio, discussing the painting with their friends. Loulou keens quietly and Georgette picks him up.

Her husband has become so famous that people who are not close ask, often, how things are going. Unlucky that her husband is in such pain that he can’t say anything puckish, as he might have before. She tries to answer with dignity and for both of them. But saying that things are “sheer muck” can’t perform the same trick as “pure shit.” This she can admit exclusively to Loulou.

he doesn’t feel like a white page, but colorless to the point of being totally clear: her heart is a tear, as in a rip, and her mind is liquid, as in a tear. Loulou sits in her lap, a warm sapience, demanding nothing; their silence is severe.

Georgette (Affiche)

Georgette looks like an advertisement for cigarettes: swan-neck erect, smoke tucked between manicured middle and manicured index, eyes more celestial than the sky behind her. Her skin of alabaster will never crack. Even the stylized clouds look to be of some fashionable brand. Her husband got his start designing posters in 1918, so no wonder. In life her hair really is that red, and in the picture he’s done its magnificence in waves so thick they suggest ancient sediments in some tawny canyon.

Her hair, she thinks, regarding their little dog Loulou, is the same color as the fur of the most popular Pomeranians. Queen Victoria’s Pom was red, so red became chic. René insisted, when they got their first shared pet, “Georgette, you’re so pretty, no other creature could compete,” and so Loulou and Loulou and Loulou—each Pom in succession—has only ever been black or white or black or white. Hair versus fur, fur versus hair. Georgette would not have cared, at first, had they shared a palette, though now she admits it might be hard to get used to.

Uxorious means showing an excessive or submissive fondness for one’s wife. Mag’s friends accuse him of uxoriousness. Their kidding is fond, Georgette understands. Love is less hard when the ardor can be indiscreet. There’s no feminine equivalent for how a wife regards her husband, which seems to Georgette discretely unfair.

Loulou has a plumed tail and a ruff at the neck, as though clad in maribou. Every day, Georgette feels grateful to Loulou: friendly and playful, loving and protective. It bites her heart to know that each dog will get to spend his whole life with her, but she will not get to spend her whole life with each of them. Only one, she supposes, will outlive her. If a new acquaintance is dismissive of the pain of the death of a pet, Georgette knows immediately: they will never become a friend.

Poms have long been popular among royalty. René has long treated Georgette like a queen. When they are out walking Loulou, he buys her treats: chocolates, little bird statuettes, and packs of her favorite cigarettes.

Advertising is a visual language: bright colors, flat forms, and efficiency efficiency efficiency. It knows, like this poster, that smoking isn’t sexy; rather, smokers are sexy.

Kathleen Rooney is a founding editor of Rose Metal Press, a publisher of literary work in hybrid genres, and a founding member of Poems While You Wait. Co-editor with Eric Plattner of The Selected Writings of René Magritte, forthcoming from Alma Books (UK) and University of Minnesota Press (U.S.) in 2016, she is also the author of seven books of poetry, nonfiction, and fiction, including, most recently, the novel O, Democracy! (2014) and the novel in poems Robinson Alone (2012). Her second novel, Lillian Boxfish Takes a Walk, will be published by St. Martin’s Press in 2017.