The Postal Origins of Text Messaging

Jim Ross

The introduction of the penny black adhesive postage stamp in 1840, coupled with the requirement of prepayment by senders, allowed England to implement a relatively trustworthy, inexpensive system for shipment of letters. Other nations quickly followed suit, such as the United States in 1847 and France in 1849.

Germany inaugurated picture postcards in 1893 and soon began mass-producing them for export. Within a decade, the picture postcard—the mailed equivalent of text messaging—had been adopted nearly worldwide.

At first the picture postcard was a deficient vehicle for messages because its undivided back was reserved for the recipient’s address. Only a small percentage of cards were designed to reserve a white space for a message on the picture side, so more often the message had to be worked into or around the picture on the front. Some senders took on the challenge of incorporating their words and micro-drawings so transparently into the picture that they came across as integral to it.

By around 1905, most European countries had adopted the divided back, with the left side reserved for the message and the right side designated for the recipient’s address. The United States approved this left/right division in 1907, allowing senders a message space and the option of keeping the picture side free of extraneous comments and markings.

Some people refused to accept the intent behind picture postcards and tried to cram a full-fledged letter into a tiny message space. This worked effectively for small-minded people. Fortunately, most people crafted shorter messages. A postcard message might include one or more of the following elements and a host of others:

- For [Christmas, Chanukah, Easter, Passover], we had a festive meal. We ate [turkey, ham, chicken, duck, lamb, leftovers].

- Everybody was happy to have a gift to open. Your letter was your gift.

- If I was going to get you something, what would you wish for?

- [Mom, Dad, Sue, Larry, Spot the dog, my horse Flicka] has [the flu, scarlet fever, measles, whooping cough, smallpox, strep throat, typhoid, consumption, hardening of the arteries, hoof and mouth] but we hope [he, she] will recover.

- I hope everyone there has gotten over [the flu, scarlet fever, measles, whooping cough, smallpox, strep throat, typhoid].

- [Mom, Dad, Sue, Larry, Spot the dog, my horse Flicka] died. A few people came to the funeral [where we worship, at home, at the cemetery, in the barn]. Sorry we couldn’t let you know in time, not that you could’ve come.

- The undertaker died. With so many people sick, that came as a rude shock.

- Is it snowing there? It is here. It’s white and dazzling outside. Also taking lots of coal to keep us warm.

- This summer is so interminably hot and humid, I don’t know how we’ll survive.

- I love the smell of [fresh-cut grass, cinnamon, hot chocolate, the sea, gasoline].

- I’ve been really busy [sewing, making pies, planting crops, keeping the shop].

- Between working [6,9,12,15,18] hours a day and raising [two, four, six, eight] children, it’s hard to find time to sit and think. Sorry I haven’t written a real letter.

- Did you have the visitor you expected?

- Can you come see me soon?

- I feel homesick just knowing you’re there and I’m here.

- My heart sinks every time I realize you won’t return to this [village, city, region, country] for [a month, a season, a year, the duration of the war, an indeterminate amount of time].

- Do you like this postcard? Tell me what kind you’d like me to send next. I like [towns, animals, soldiers, children, trains, ships, actors, comics].

- Send me a postcard if you want me to send you the [medicine, machine, book, swatches, seeds, dress].

Some postcard messages were typically sent to those living nearby:

- I really enjoyed [seeing, meeting, talking with] you.

- Next time, I’ll [arrive on time, stay sober, be more daring, be more myself].

- I can’t wait to see you again [this Saturday, whenever you invite me].

- I prefer never hearing from you again [ever, after next time].

- Didn’t you think yesterday’s [torrential rain, thunder storm, hailstorm, eclipse] was [exciting, terrifying, destructive, inspiring]?

- I’m catching the train tomorrow in Hagerstown at 8:30 a.m., which should reach Baltimore by 10:30. If I walk straight to Lexington Market and pick up a meat pie for lunch, I should reach your house by 12. I’ll be hungry. I hope you will too.

The last message about picking up the pie attests to the speed and efficiency with which the postal service once operated (or perhaps to the overly optimistic expectations of its patrons).

During times of war, many countries printed postcards displaying war scenes, patriotic images, or happy homecomings specifically for those on active duty to send home. “Host” countries also often printed postcards designed for Prisoners of War (POWs) to write and send. To create the impression that POWs were being treated well, such cards showed POWs writing letters, engaging in sports, dancing with each other, lounging in spacious quarters, cutting each other’s hair, performing stage plays, or playing musical instruments.

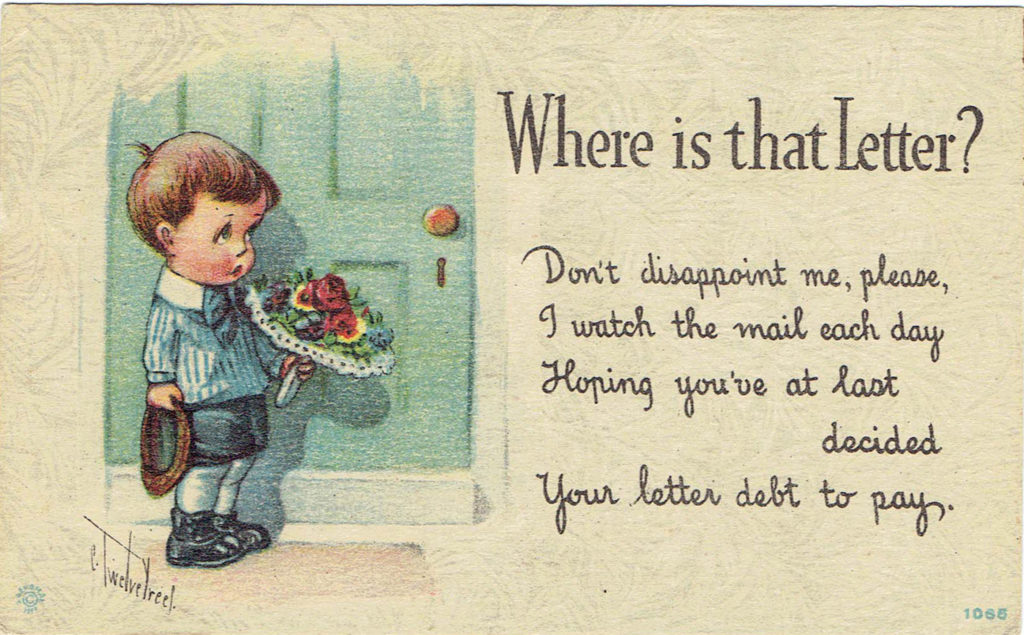

The postcard was often designed explicitly as a prelude to a letter. Some carried an impatient printed message, “When are you going to write the letter you owe me?” Others simply said, “You know I know I owe you a real letter. For now, this postcard will have to suffice.”

Click here for a gallery of antique postcards, selected from the author’s collection.

Jim Ross enjoyed a long career in public health research. During one ten-year stretch, he collaborated with Bar-Ilan University and various universities throughout Europe on research related to child health. Professionally, he authored scores of articles published in peer-reviewed journals, book chapters, and anthologies. After retiring in early 2015, he jumped back into creative pursuits to resuscitate his long-neglected right brain. He’s since published 45 pieces of nonfiction, several poems, and 150 photos in over 50 journals in North America, Europe, and Asia. His publications include 1966, Lunch Ticket, Make Literary Magazine, Meat for Tea, Stoneboat, The Atlantic, and The Sun. Jim and his wife–parents of two health professionals and grandparents of four toddlers–split their time across three states in the United States. He hopes to move more in the direction of combining photos with stories.

Jim Ross enjoyed a long career in public health research. During one ten-year stretch, he collaborated with Bar-Ilan University and various universities throughout Europe on research related to child health. Professionally, he authored scores of articles published in peer-reviewed journals, book chapters, and anthologies. After retiring in early 2015, he jumped back into creative pursuits to resuscitate his long-neglected right brain. He’s since published 45 pieces of nonfiction, several poems, and 150 photos in over 50 journals in North America, Europe, and Asia. His publications include 1966, Lunch Ticket, Make Literary Magazine, Meat for Tea, Stoneboat, The Atlantic, and The Sun. Jim and his wife–parents of two health professionals and grandparents of four toddlers–split their time across three states in the United States. He hopes to move more in the direction of combining photos with stories.