Corresponding Authors (Letter 4 of 9)

In response to:

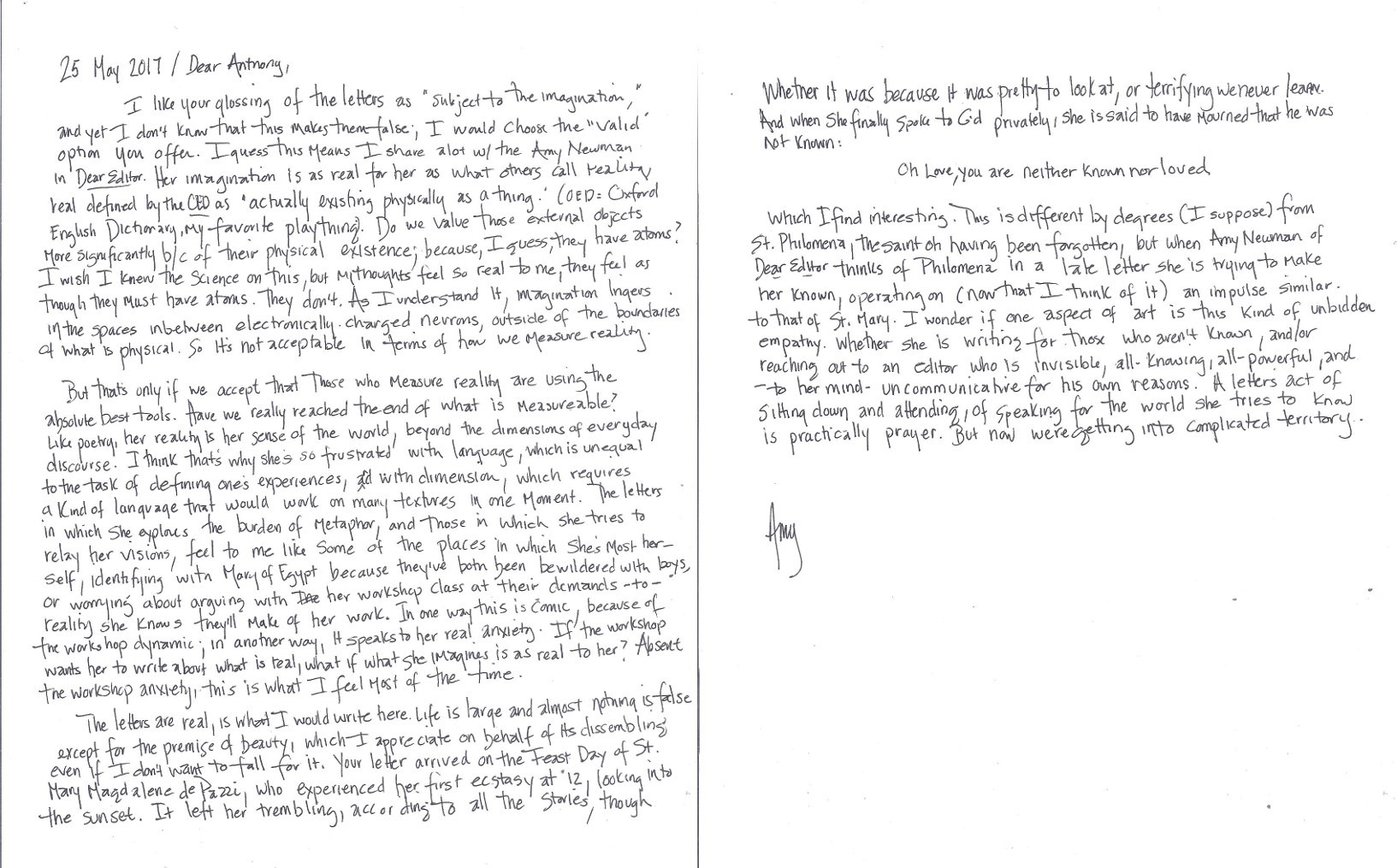

25 May 2017

Dear Anthony,

I like your glossing of the letters as “subject to imagination,” and yet I don’t know that this makes them false; I would choose the “valid” option you offer. I guess this means I share a lot with the Amy Newman in Dear Editor. Her imagination is as real for her as what others call reality, real being defined in the OED as “actually existing physically as a thing.” (OED = Oxford English Dictionary, my favorite plaything). Do we value those external objects more significantly because of their physical existence; because, I guess, they have atoms? I wish I knew the science on this, but my thoughts are so real to me, they feel as though they must have atoms. They don’t. As I understand it, imagination lingers in the spaces in between electronically-charged neurons, outside of the boundaries of what is physical. So it’s not acceptable in terms of how we measure reality.

But that’s only if we accept that those who measure reality are using the absolute best tools. Have we really reached the end of what is measureable? Like poetry, her reality is her sense of the world, beyond the dimensions of everyday discourse. I think that’s why she’s so frustrated with language, which is unequal to the task of defining one’s experiences, and with dimension, which requires a kind of language that would work on many textures in one moment. The letters in which she explores the burden of metaphor, and those in which she tries to relay her visions, feel to me like some of the places she’s most herself, identifying with Mary of Egypt because they’ve both been bewildered with boys, or worrying about arguing with her workshop class at their demands-to-reality she knows they’ll make of her work. In one way this is comic, because of the workshop dynamic; in another way, it speaks to her real anxiety. If the workshop wants her to write about what is real, what if what she imagines is as real to her? Absent the workshop anxiety, this is what I feel, most of the time.

The letters are real, is what I would write here. Life is large and almost nothing is false except for the premise of beauty, which I appreciate on behalf of its dissembling even if I don’t want to fall for it. Your letter arrived on the Feast day of St. Mary Magdalene de Pazzi, who experienced her first ecstasy at a 12, looking into the sunset. It left her trembling, according to all the stories, though whether it was because it was pretty to look at, or terrifying, we never learn. And when she finally spoke to G-d privately, she mourned that He was not known: “O Love, you are neither known nor loved” which I find interesting.

This is different only by degrees (I suppose) from St. Philomena, the saint of having been forgotten, but when Amy Newman in Dear Editor thinks of Philomena in a late letter she is trying to make her known, operating on (now that I think of it) an impulse similar to that of St. Mary. I wonder if one aspect of art is this kind of unbidden empathy.

Whether she is writing for others who aren’t known, and/or reaching out to an editor who is invisible, all-knowing, all-powerful, and —to her mind—uncommunicative for his own reasons. A letter’s act of sitting down and attending, of speaking for the world she tries to know is practically prayer. But now we’re getting into complicated territory.

Amy