An Interview with Bianca Stone

Questions by Ariel Kahn

Bianca Stone is a poet and visual artist. She is the author of the poetry collections Someone Else’s Wedding Vows (Tin House/Octopus Books, 2014), Poetry Comics from the Book of Hours (Pleiades Books, 2016), and multiple chapbooks. She is also a contributing artist for a special edition of Anne Carson’s Antigonick. With her husband, the poet Ben Pease, Stone co-edits the small poetry press Monk Books, and with Pease is executive director of The Ruth Stone Foundation, an organization dedicated to the furthering of poetry and the arts and the preserving Ruth Stone’s legacy and house in Vermont.

You started off writing purely prose poetry. How did you shift into illustrating your work?

Well, to be clear, it’s not limited to prose poetry, but just poetry in general. I wouldn’t say I started off writing purely poetry—since, for me, it’s always been poetry and art at the forefront of my life. Rather, the shift was intentionally putting the words of my poems into my drawing and calling it something. In graduate school at NYU around 2008, Matthew Rohrer introduced me to the term “poetry comics” and I felt this spark of inspiration. Giving something a term, however undefined, can be life-altering. It’s like hearing the term “depression” for the first time. It’s like OHhhhhhhh. And there’s so much imperfection in labels, but that too is what’s so fun about it. You can continuously argue and discuss and debunk and rebuild it. So after I heard this term I began to combine poetry and art with great intention. And calling it something gave me permission to bring my art into my (let’s call it) “professional” life as a writer.

I mean, here were these two arts I’d loved doing ever since I could hold a pen, and now I could experiment with what it really meant to combine them; how to do both justice; how to complicate and further the power of each medium. I want to see what the limits of both are, and then exploit that knowledge. Turn it inside out. Break it apart and look at how it work. We have all this power as human beings to think creatively. This silly term (poetry comics) was—is—just what enabled the leap in my mind to do new things. No matter if there’s no definition of what it is. Thank god there’s no clear definition.

There is a warm, playful tone to many of your images, in counterpoint to the edgier tone of your poems. Do you feel your words and images come from different places, or express different aspects of yourself?

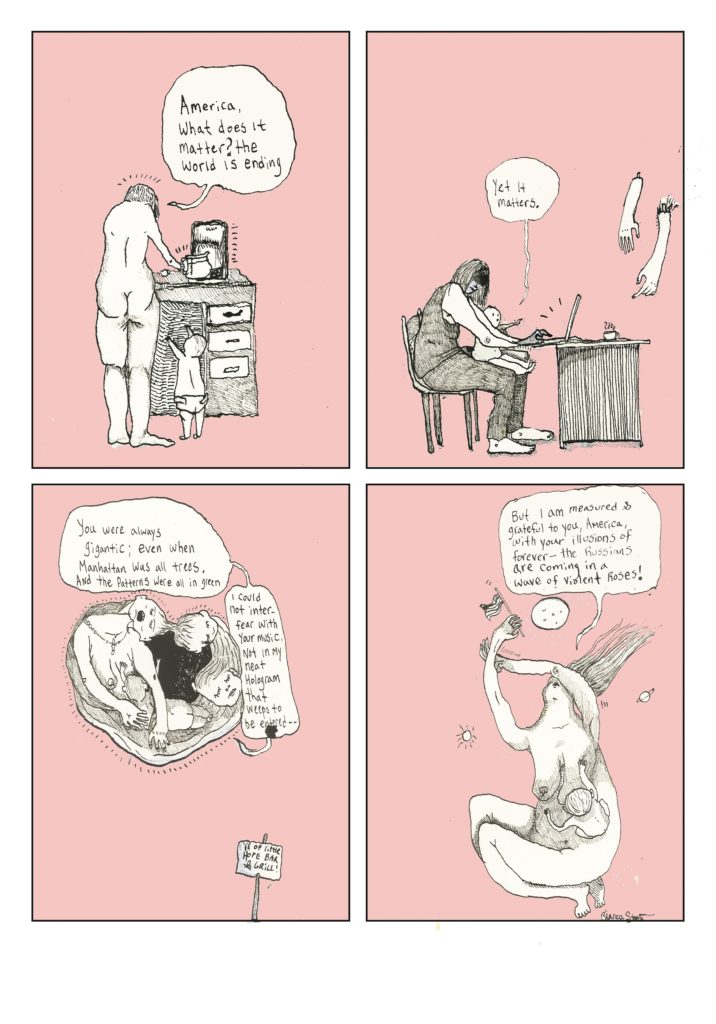

There’s so much that can be expressed with visual images that just can’t be in words. And what’s powerful about words alone is that the reader can create the visual in their mind. This of course is a well-known fact about the power of poetry. And why so many people get it wrong trying to “understand” it. But in any case, I try in my poetry comics to not take away that negative capability; that mystery in the words, and instead think of the images as I would a line of a poem.

I think you’re right about the tone. I’m more apt to allow for irony in the juxtaposition between playful and dramatic. I like to counteract the tones; they come from the same place, but translate differently once out in the open. Writing poetry requires a certain amount of something–not necessarily work, but something– in the head; even two words coming together, that power when they are beside one another–it’s a very specific mode of the brain that’s turning on. Whereas with images I feel I can let my mind wander while I do it. There’s a totally different area sparking when I’m doing this. Different demands of mindfulness.

Your poems often circle the dance of intimacy and relationships. Does this theme lend itself to a visual dimension?

Oh yes–even just the words you used invoke visual images for me! “Dance” is so present in my artwork. I find the movement of bodies to be one of the main themes of my work. Perhaps it’s my influences? (Chagall, who has such amazing movement in his work.) Dance is also so linked to poetry, that rhythm and emotion and structure. And also the connection of people in my work—I like to have people up against one another, smashing together. Or facing away, towards, in and out. That desire for connection in the art is in the poems too. But really you’re talking about intimacy. It’s that yearning to connect, to be understood, finally, maybe, that brings out these traits in my work. Although I’m also so aware of the futility of it, because we’ll never truly connect with others like we have the opportunity to connect inwardly….so that DANCE continues, continues, continues…

You bring in a powerful sense of the non-human and hybrid other in your work, from mutation to animals. Is this a vision of an imagined future, or a commentary on our relationship to the non-human world? Both?

I feel dissatisfied by the isolation we face in our society from the natural world. And I think that tension is where a lot of depression, anxiety and grief come from. And of course, therefore, creative response comes in. Thankfully we have that…Maybe it is a kind of vision of the future, or at least a hallucination of the possibilities of returning to the natural world. It isn’t a commentary, but a reaction.

You draw on a huge range of comics and cultural iconography, from superheroes to religious imagery. What connective tissue is there for you between so-called high and low culture?

If you take a walk through the Renaissance exhibitions at the Metropolitan Museum, you’ll see how creepily similar their methods were to comic strips. There’s drama, hyperbole, posing; but more telling is there’s often panels, or triptych, or frescos depicting scenes that move in a linear order—just like a comic strip! Look at the Sistine chapel!

And meanwhile, I could sit around defending comics as high art too, but what’s the point? It’s not even “dorky” anymore to like comics. It’s a billion dollar industry and virtually everyone likes superhero stuff. What I’m more interested in in my work is using tools from those genres and applying them to other surfaces. I like the methodology of comic strips, of high art, but I’m not schooled in either one. I only know what I’ve taught myself, what I’ve picked up along the way, and with poetry and art, I’ve never been one to feel I needed to know EVERYTHING before I actually started DOING IT. Like with guitar, you can write a song with two chords. And it can be good. I say this, because I don’t see anything stopping me from plucking from different traditions, if they really speak to me.

You use a lot of watercolour and ink. What draws you to these media in particular? What effects do you feel they create?

The pen has always been my medium of choice. As a teenager, I practiced crosshatching for hours. Literally. My favorite was a plain Bic pen, and at most a micron. That floated me for a looonnng time. But after grad school I won a NYFA Grant for my art, I went out and splurged on some art supplies. It changed my life. I started using a nib and ink pot on thick, nice watercolor paper. I loved how violent it was, scraping the ink across the paper, flicking it so it spattered. I could work with my messiness, my mistakes. And then watercolors allowed me to still work with my ink, and to color in.

When I was collaborating with Anne Carson on Antigonick, I started exploring different methods of watercolor and ink, and training hard to hone my craft. Ever since then (around 2009?), I’ve almost exclusively worked in pen/ink/watercolor.

And isn’t that important? To actually finally invest in our art? The things we truly care about? Not tech crap or retirement. What if we actually allow in the materials we need to make something? It’s not about money, really, but it’s about committing to next level; to say to yourself: this isn’t about drawing in my private journal anymore. This is bigger than my journal. Just as I made that decision to make my poetry a public act, my art had to evolve.

Your images are sometimes so powerful and arresting that they often seem to have their own centre of gravity, changing the nature of the poem, so that the text becomes a kind of commentary. How do you see the relationship between your words and images? Does it depend on the poem?

I love that reaction. And of course it changes everything when you put an image beside a word. Imagine the line “My mistress eyes are nothing like the sun.” And then imagine someone puts that line beside, say, a woman leaping off the back of a train into the arms of a bear–or a mountain all alone in the distance. Imagine that line in a word bubble coming out of the mouth of a tired old woman–the options are limitless, but you make that choice as an artist. The poem will determine where your mind goes as the person creating this third thing; this third work of art that is not the poem, or the art, but something else now. Sometimes I start using a poem and it’s just not working, and I need to choose another. It’s a delicate choice; a subtle, sonic thing.

Your poems sometimes use comics panels, but the characters burst away from these, into the white space around them. Do you see the panel as confining?

Technically, (literally?) it is confining! But just like the forms of poetry that make it poetry, it’s a necessary confine. The great (much quoted) Scott McCloud talks a lot about the panel being important, in his book Understanding Comics because of that white space (gutter) between panels. The blank space creates meaning. That space where we don’t see what’s happening is where the magic is. It’s just like Keats’ negative capability. It’s just like a line break. Like the poetic form, or just the form the poem makes on the page: stanzas, etc. So I know that space, and the confined space, is important. That said, for me, I don’t feel beholden to it. It’s not that it’s confining I don’t think….It’s just that I feel often times a discomfort in my comics with the technical rigors of making boxes, which I feel like I’m not good at. This is something I’m interested in exploring more and challenging myself with. I want to make better panels. I want to use them more.

How much are the comics artists and poets whom you know talking to one another, or working together?

There’s a lot of effort to make a bridge, but I’m not sure how strong it is. It’s always been the case that poets and artists have interacted and collaborated, or at least drank together. One strong example is the New York School poets, and among them Joe Brainard, who was a great artist with so much poetry and comics in everything he did. For comic artists and poets coming together in particular, I know my good friend Alexander Rothman does a lot of great work in that area. He knows a lot of the comic arts scene and he’s on a MISSION for poetry comics. It’s wonderful to see. For me, I stay pretty solidly in the poetry scene. I wish I knew more artists. I’m hoping to change that with some classes next year, engaging more with studying the craft of comic arts.

Where would you send readers new to poetry comics?

Check out Ink Brick magazine. Alexander does a stellar job finding people and the website provides a lot of leads to other things comics-poetry. Also most major journals now publish them, including Poetry Magazine!

There is a strong sense of movement, of development, in your poetry and images. Where are you headed next?

I’m working on animation! I know next to nothing about the tech, so it’s slow and laborious…I’m collaborating with a filmmaker Nora Jacobson who is making a film about my grandmother, the poet Ruth Stone. I’m so excited to challenge myself with this. As always I’m writing poetry. My new poetry collection The Mobius Strip Club of Grief will be out from Tin House in February.

Ariel Kahn is a Senior Lecturer in Creative Writing at Roehampton University, where he teaches a course on writing for comics and graphic novels. He is a contributor to The Jewish Graphic Novel (edited by S. Baskind and R. Omer Sherman; Rutgers University Press, 2008), has written regularly on comics and graphic novels for journals including the International Journal of Comic Art and Critical Engagements, and was a contributor to Paul Gravett’s 1001 Comics You Must Read before You Die (Cassell, 2011). He was a contributor to the Eisner-winning Graphic Details: Jewish Women’s Confessional Comics in Essays and Interviews (Edited by Sarah Lightman, McFarlands, 2014) and Drawn and Quarterly: Twenty-Five Years of Contemporary Cartooning, Comics, and Graphic Novels (Ed. Tom Devlin, 2015).

Ariel Kahn is a Senior Lecturer in Creative Writing at Roehampton University, where he teaches a course on writing for comics and graphic novels. He is a contributor to The Jewish Graphic Novel (edited by S. Baskind and R. Omer Sherman; Rutgers University Press, 2008), has written regularly on comics and graphic novels for journals including the International Journal of Comic Art and Critical Engagements, and was a contributor to Paul Gravett’s 1001 Comics You Must Read before You Die (Cassell, 2011). He was a contributor to the Eisner-winning Graphic Details: Jewish Women’s Confessional Comics in Essays and Interviews (Edited by Sarah Lightman, McFarlands, 2014) and Drawn and Quarterly: Twenty-Five Years of Contemporary Cartooning, Comics, and Graphic Novels (Ed. Tom Devlin, 2015).