City of Refuge

Adi Sorek

Translated from the Hebrew by the author and by Marcela Sulak

The following is a segment from a project in progress called City of Refuge.

In the Talmud, a City of Refuge is a city in which someone who has accidentally killed another person can claim asylum, or find refuge. In Hebrew, the words for “refuge” and “shelter” are the same. Therefore, this project arose from intertwined questions: What is a shelter? And what is a City of Refuge?

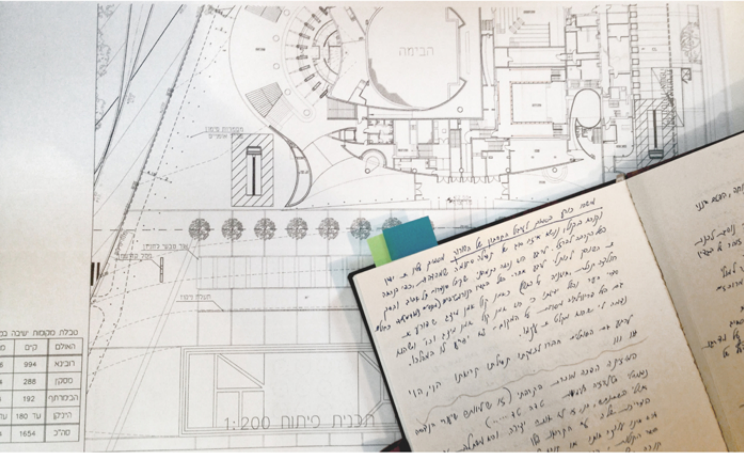

The texts included in this project are based on a diary that I wrote over the course of a year, during which I sat in the center of Tel-Aviv at Ha-Bima Square in the mornings and recorded what was happening before me. The diary begins in the fall of 2014, at the end of the last Gaza War, and ends in the summer of 2015.

Ha-Bima Square, home of Ha-Bima theater, has a hidden fallout shelter dug beneath it. While thinking about it, I asked myself: Is a shelter merely a technical and physical structure, or can a shelter be thought of as a linguistic, literary, and intellectual construct? And which type of shelter is, in fact, more protective?

I began by attending to the outline of the doors leading to the underground bomb shelter—doors designed as part of the plaza floor and therefore paved in tiles, covered, like secret doors. They open during wartime and close in times of “peace”.

In wartime, the underground area is supposed to be a shelter. At other times, it is a parking lot.

In addition to my post-war diary, City of Refuge contains other fragments, such as reflections on the Talmudic notion of the City of Refuge: Who are the accidental killers invited to the gates of the city? What is the role of the intellectuals (the Levites) who are responsible for the city, but not its owners? What makes it possible to replace and reconfigure murderous blood connections, so that something can go beyond murderous blood ties?

I perceive the texture of the resulting text as a kind of tile, or mosaic. During the process of writing, the tiles of Ha-Bima Square merged and separated repeatedly from those of the City of Refuge, and the oscillation between them led to a mental wandering that inquires about the connections, gaps, and passages that exist or have the potential to exist between the text and the everyday space.

Tzabar (صَبَّار, צבר)

Based on a diary entry from March 11, 2015

In Arabic the meaning of the word Tzaber (صَبَّار) is related to patience, tolerance and endurance. In Hebrew Tzabar (צבר) is a verb that means to accumulate (Litzbor) and is related to the Tzabar plant (or Sabra),* perhaps due to its ability to accumulate liquids. Or perhaps because of the web of entanglements in the word as it appears in the Semite languages of Ugarit, Aramaic, Hebrew and Arabic (Ivrit and Aravit) with regard to gathering and congregation. In Modern Hebrew “Tzabar” is the nickname for a Jew born in Israel; and also a plant that is associated with the emptied Arab villages – for generations dense fences of the Tzabar have marked the village boundaries.

While sitting in Ha-Bima square I look back at the fleshy body of a Tzabar planted in the garden in the heart of the city, and its big wounded leaves, the life already infected with death. The sun is wintry, soft, a catalyst for reflection. My eyes merge with the thick leaves, moving over the severed points of its thorns and the plant’s connective regions.

Do we have blood relations with plants? Are such connections possible? If we had a blood relation with the Tzabar, a relationship of another order, would we become infused with its patience, its ability to endure, its tolerance, its ability to gather, to congregate? If we were able to develop blood relations with the Tzabar, what would they teach us? What would accumulate in our memories?

* The scientific name of the Sabra is Opuntia ficus-indica. Like most cacti it was introduced to the region between the 16th and 17th centuries by Spanish travelers and conquerors.

Note: I thank Maya Klein and Karen Marron for their help in shaping the text and adapting it into English.

Adi Sorek (born 1970) is the writer of the novel Nathan (2018, Keter Press) and of the books Sometimes You Lose People (2013, Yediot Books Press, winner of the Goldberg prize), Internal Tourism (2006, Yediot Books Press), and Seven Matrons (2001, Yediot Books Press, finalist for the Moses prize). She is also a founding editor of the experimental prose series Vashti for Resling Press and a predoctoral researcher in Tel Aviv University’s Literature Department. She lives in Tel-Aviv.